How Saving Family Photos Helped Three Generations of Photographers Preserve a Remarkable Legacy

Sunset near the Narrows Bridges, Tacoma, Washington, 2016.

He reaches up and gently pulls a tuft of his hair to show me how easily it falls out. It’s grey now, his hair. It wasn’t last April, when we met at that little café for my 20th birthday. I sat across from him, secretly angry he was ruining the first day of my twenties by talking about his arm again. Or his shoulder. Or, dear god, what he called his “backside.” (It’s because you’re old and that’s what happens. It’s my birthday, can’t we pretend everything is fine?, I thought.) I’m ashamed of my thoughts but they still come, coursing through my mind like the cancer coursing through my grandfather’s body on that April afternoon. It falls easily into palm of his hand, his hair. “Isn’t that the darnedest thing?”

By the time we learn what’s causing the bone pain, the cancer is too far advanced to do much except make him comfortable. He makes me try it, pull out his hair, to prove to me it doesn’t hurt. I reach up but instead of pulling out his hair, I touch his cheek. It takes him by surprise, this intimate gesture. I ask if he’s scared. He says he is, a little. “I’ve never died before.”

The day he dies, I’m a hundred miles away having surgery on a wrist I’d shattered the week before. Through the haze of the anesthesia, my sweet friend Jenny whispers she has something to tell me. “He’s gone,” I say, “isn’t he?”

Twenty years later, the man I knew as my grandfather is hard to separate from the stories that remain a part of our family’s narrative. After his death, it becomes easier for his children (my aunts and my father) to reveal the sometimes-brutal nature of his parentage. I don’t blame them, of course, for processing their complex emotions, but the result is that I feel like he died twice – the physical death followed by the death of the character he played in our family story, or at least my version of it.

Our family’s story is as complex as anyone else’s – with all the pain, hope, love, joy, loss and fear any family faces. The difference is that our story is uniquely preserved through images and a deep connection to the craft of photography, now three generations strong. In fact, I believe saving family photos helped three generations of photographers preserve a remarkable legacy.

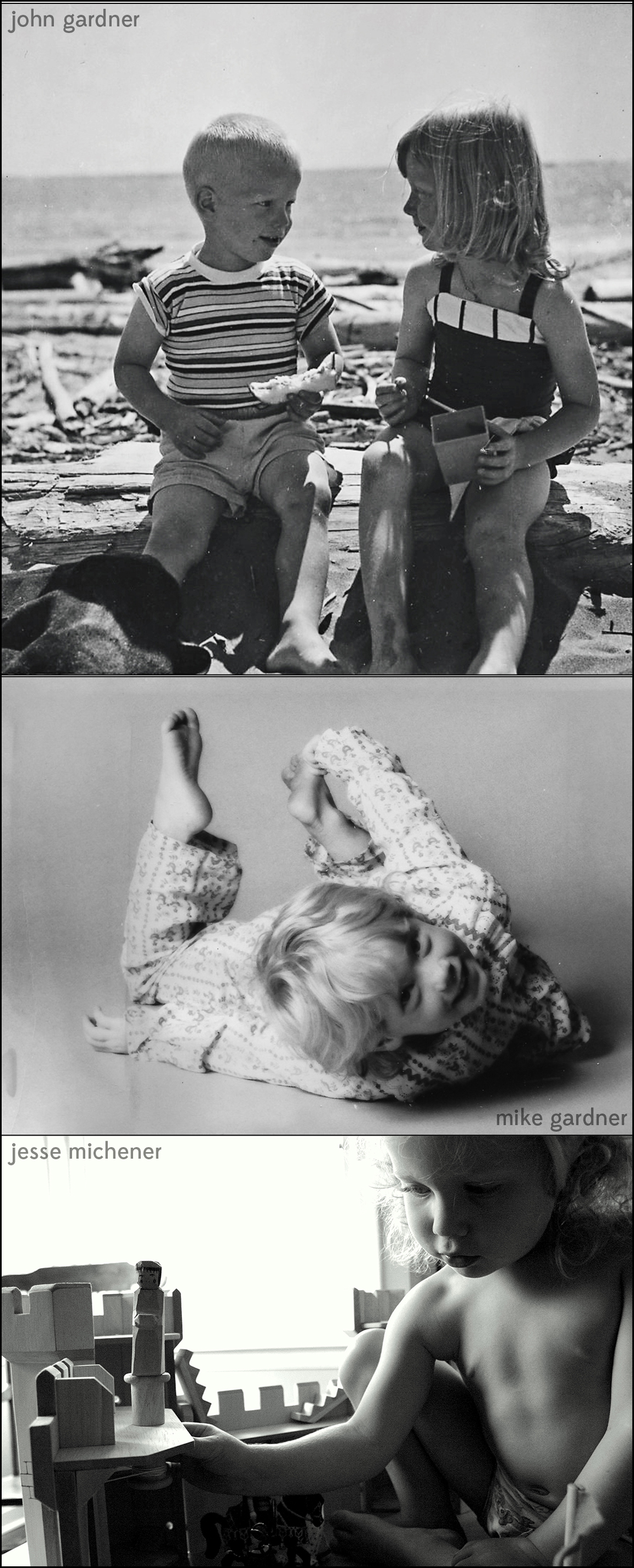

Three generations of photographers and their children (Top: my dad and aunt, 1958; middle: me, 1977; bottom: one of my daughters, 2003).

Growing up within a family of photographers meant I was exposed (forgive the pun) to both the mechanics and aesthetics of the craft. Photography is built on three separate but related pillars: composition, storytelling and technical aptitude. It is through these pillars that I began to understand my grandfather.

And ironically, the act of digitizing two-dimensional images is the only way to develop a three-dimensional view of the person he was – not as a father or grandfather, but as the man behind the lens.

The same holds true for my father, although I’ve also had the benefit of a real-time relationship with my dad. Perhaps most importantly, I can use that same lens of understanding to learn more about myself and the roles I fill in our family and in the world.

It was no easy task, convincing my grandmother to let me take temporary possession of the thousand or so family images crammed into an old wooden trunk. Even in a photographer’s family, it seems few images make it into albums or are properly organized. She nearly relented when I argued the the pictures were quickly degrading from mold created by water damage, but she only agreed when I promised to make her an album and share the files with the rest of the family. My skin crawled after a few minutes with the images; my chest wheezed in protest to the invisible but copious mold. From over a thousand images, I scanned about four hundred. Scanning itself went quickly, thanks to an investment in a flatbed scanner that could detect individual images as save them as separate files in one scan. After scanning, I sorted the digital files into folders by decade. Next, I color-corrected each shot and created a black-and-white conversion for consistency.

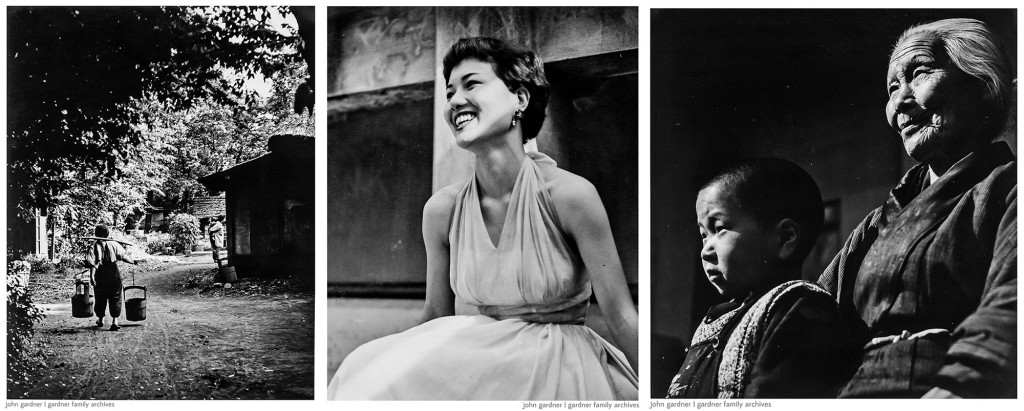

My grandfather’s photos (left-right) Child carries water in a village outside of Tokyo, Woman in western dress, Tokyo, Grandmother & grandson, Japan, c. 1952.

The project I thought would take a month or two took nearly six months. Soon it was clear that Grandma’s album needed to be split into two volumes: one that focused life before they had kids and one that chronicled their growing family. It took another six months to curate images for the first book. Sure, it could have gone more quickly, but once you hop down the online-ancestry-research-rabbit-hole, it’s difficult to move fast.

Faces long disconnected from stories suddenly were alive again. Family members whom I’d only known as elderly appeared before me, lit by the golden light of youth. Never before had I been so thankful for handwritten notes on the back of pictures, even when the ink bled through.

Linking fragmented family histories and partially-remembered facts with the online ancestry resources, I even solved a family mystery: what killed my great-uncle’s two children when they were just toddlers? Tay-Sach’s most likely. The especially cruel disease is found in certain populations, including the French-Canadians in New England and eastern Canada, where my family lived for generations.

The greatest discovery, though, was seeing long-past or aging family members with fresh eyes. Outside of his stoic role within our family, my grandfather was a rowdy college kid. He had friends; he shot for the student newspaper; he looked kind and fun and handsome. My grandmother, too, came alive within the pages of the album. She was a fashionista; she was happy; she was her truest self, not the slowly-withering woman I see before me now. Family stories span decades long since past, but are just a breath from where I was twenty years ago and where my own children will be in a mere blink.

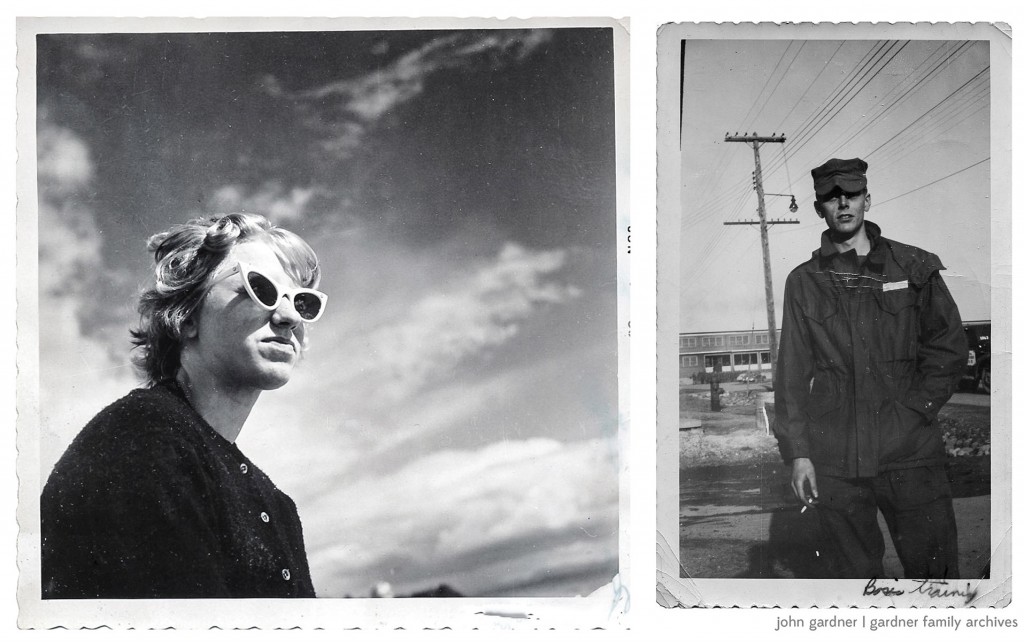

Grandma in the late 1950s (left) + Granddad at basic training, circa 1949 (right)

I was able to present my grandmother with the finished album last month, about a year after starting the project. Her eyes regained some of their former light as she recounted her role in the grand narrative she held in her hands.

The complete family album – more than just a collection of images – means our story will continue to be a reminder that none of us are truly alone.

The complete family album – more than just a collection of images – means our story will continue to be a reminder that none of us are truly alone.

You were here, the pages confirm.You were loved.You are missed.

About the Author: Jesse Michener is a writer, photographer, teacher, mother, wife, fly-by-the-seat-of-her-jeans kinda gal. She’s a third-generation photographer who maintains an active freelance career in addition to teaching full-time. Jesse loves people and their stories and, if she were to meet you today, she’d want to hear yours. She’d shake your hand upon greeting you and hug upon leaving, because that’s what stories do: they bring people closer together.Jesse and her brood reside in Tacoma, Washington. She has degrees in theatre and education from a private university whose loans she may never be able to repay in this lifetime. She met her husband, Mike, on the stage of that university and he’s been her sidekick for over 17 years. The best thing about their relationship? They each think the other is hilarious! This helps them stay fairly sane when the world, especially their little world, is going nuts. Jesse and Mike have three daughters – Violet, Zoe and Eleanor. The family of five live in a house that has one (highly-valued) bathroom.

About the Author: Jesse Michener is a writer, photographer, teacher, mother, wife, fly-by-the-seat-of-her-jeans kinda gal. She’s a third-generation photographer who maintains an active freelance career in addition to teaching full-time. Jesse loves people and their stories and, if she were to meet you today, she’d want to hear yours. She’d shake your hand upon greeting you and hug upon leaving, because that’s what stories do: they bring people closer together.Jesse and her brood reside in Tacoma, Washington. She has degrees in theatre and education from a private university whose loans she may never be able to repay in this lifetime. She met her husband, Mike, on the stage of that university and he’s been her sidekick for over 17 years. The best thing about their relationship? They each think the other is hilarious! This helps them stay fairly sane when the world, especially their little world, is going nuts. Jesse and Mike have three daughters – Violet, Zoe and Eleanor. The family of five live in a house that has one (highly-valued) bathroom.

You can follow along with Jesse on her many adventures via Twitter and Instagram.

5 Comments

hILARIE says:

February 22, 2016 at 5:54 pm

WHAT A BEAUTIFUL POST! tOUCHING, PROFOUND, INFORMATIVE… GREAT CONTENT! tHANK YOU FOR SHARING.

Fred says:

February 23, 2016 at 5:05 pm

Beautfully written. If i may ask, what scanner did you use?

rachellacour says:

February 24, 2016 at 3:24 am

Great question, Fred! I will ask Jesse if she can reply here.

Nicole Dyer says:

February 28, 2016 at 2:19 am

Thanks Jesse, I loved this. Your writing is gorgeous. I like how you created black and white versions of the scans for consistency. Great idea. ONe of my favorite reads of the week – and I featured it on my blog. http://familylocket.com/favorite-reads-of-the-week-27-february-2016/

rachellacour says:

February 28, 2016 at 2:22 am

😀